- Home

- Brenner, Marie

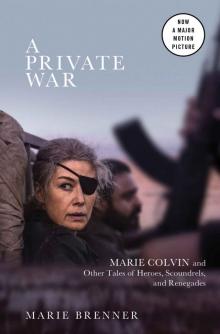

A Private War

A Private War Read online

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

* * *

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

Contents

Epigraph

Introduction

MARIE COLVIN’S PRIVATE WAR

THE BALLAD OF RICHARD JEWELL

THE TARGET

AFTER THE GOLD RUSH

FRANCE’S SCARLET LETTER

JUDGE MOTLEY’S VERDICT

THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH

HOW DONALD TRUMP AND ROY COHN’S RUTHLESS SYMBIOSIS CHANGED AMERICA

Acknowledgments

About the Author

For Ernie and for Peggy, and always for Casey and for Marie Colvin and all who put themselves in harm’s way to report the truth

“There is always one moment in childhood when the door opens and lets the future in.”

—Graham Greene

Introduction

To understand the arc of her career, you have to know how it ended.

Marie Colvin’s last assignment was in February 2012, in a ravaged war zone in Syria. She operated from what she called “a media center” in the town of Baba Amr, crouched with a few other journalists in a small building in narrow streets. The top floor had been blown off by the deluge of rockets and shells raining down from the forces of the dictator Bashar al-Assad. Now, on a Wednesday morning in the early hours, the American-born foreign correspondent who worked for decades for the Sunday Times of London awakened to the convulsions of rockets and shells around her.

The night before, she’d left her shoes outside in the hall—the gesture, her longtime colleague and friend Jon Swain noted later, would cost her life. With her was Sunday Times photographer Paul Conroy, fraught with anxiety because he was certain Colvin’s insistence on returning to Baba Amr could end in catastrophe. But Colvin was there to record it all: “Snipers on the rooftops of al-Baath University . . . shoot any civilian who comes into their sight. . . . It is a city of the cold and the hungry, echoing to exploding shells and bursts of gunfire.” There was, of course, no telephone or electricity. Freezing rain filled potholes and snow drifted through the windows during the coldest winter anyone in Baba Amr could remember, Colvin wrote. “Many of the dead and injured are those that risked their lives foraging for food,” Colvin wrote.

The essence of that detail was what mattered to Colvin most: the need to bring to vivid life the human costs of war. Sprinting through a barrage of rockets, Colvin spent a day in a makeshift clinic, interviewing victims. The Sunday Times bannered her report across two pages. Later it would be noted that hers was one of the first convincing reports predicting al-Assad’s genocide, which would overtake Syria. After her first piece was filed, Colvin mailed her colleague Lucy Fisher, “I did have a few moments when I thought, ‘What am I doing? Story incredibly important though.’ ” Mx. She demanded to return to Baba Amr and would not hear otherwise. “It is sickening that the Syrian regime is allowed to keep doing this,” she wrote her editor when she returned three days later. “There was a shocking scene in an apartment clinic today. A baby boy lay on a head scarf, naked, his little tummy heaving as he tried to breathe. The doctor said, ‘We can do nothing for him.’ He had been hit by shrapnel on his left side. They just had to let him die as his mother wept.”

“This is insane, Marie,” Conroy told her angrily when she announced she had every intention of returning. “Assad has targeted you and all the journalists.” Trained in the British military, Conroy understood the peril. He also had an acute sense of Marie’s vexed tech skills. She was a woman of a certain age, who had started her career when you dictated a story over the phone to an editor. Often, in the field, Conroy would retrieve lost files that had vanished into the nether land of her laptop. How could she ever truly understand the consequences of dialing from a SAT phone in an area where an enemy was trying to track her location? He argued with her in the tunnel, until she stalked off, saying, “Save a place for me at the bar.” Then he followed her, terrified of what could happen if he was not, as always, by Marie’s side.

* * *

I arrived in London a few days after Colvin died to write about her life for Vanity Fair. Conroy was still recovering from the explosions that almost cost him his leg. Dragging his IV poles, he forced himself to speak about Colvin at a reception at the Frontline Club, where London’s foreign correspondents meet. The next day, at the hospital, I spent hours by his bed. One of the first stories he told me took place outside Sirte in the Libyan civil war. Colvin and Conroy had been trapped for days as the troops who surrounded Libya’s strongman Muammar Qaddafi fought with those who were trying to depose the vicious despot. Minutes from deadline, in a speeding car heading for the border, there wasn’t a whisper of power they could use to transmit Marie’s copy from her laptop. The driver screamed as Conroy crawled onto the back of the car with his gaffer tape to place a booster, with sand and dust blowing in his eyes. Marie hit send. Then, both Paul and Marie screamed with relief as the car streaked down the highway. “I have never seen journalists who worked this way,” the driver told them. “Well, you have never worked with the Sunday Times,” Marie yelled.

* * *

A few words of context: For years, Colvin had dined out on her early days as a thirty-year-old reporter for the Associated Press posted to Beirut in 1986. Her first real scoop was the penetration of Qaddafi’s underground lair at the moment he was in a tense stand-off with then-president Ronald Reagan. Qaddafi was at this point an eccentric under-the-radar autocrat who posed as a Bedouin chief, then anointed himself a colonel, directing bombings across Europe from subterranean rooms underneath his palace. Colvin refused to stay with the small press pack that had converged on Tripoli, hoping to get an interview. Arriving at his palace gate, she pretended to be French and captivated Qaddafi’s guards with her dark, curly hair and reporter’s moxie. At 3 a.m., she was summoned to a hideout three stories beneath his palace garden. It contained an underground medical clinic, armored doors with automatic locks, and a throne room where Qaddafi would later lay out green shoes for her to wear. After one interview, he sent a nurse to her hotel room with a hypodermic needle. The nurse announced, “I Bulgarian; I take blood,” before Colvin could flee with her cassette tapes. The scoop made her name and brought Colvin to the attention of the Sunday Times, where she quickly rose to become one of the most acclaimed war reporters of her generation.

* * *

Colvin never wavered in the essential understanding of who she was and the importance of what she did. She could somehow use the term “bear witness” and get away with it. You can call a phrase like that grandiose and self-inflated, and sometimes people did, but Marie had a mission that she turned into a vocation, and that was to go to the most violent and dismal places on earth and bear personal witness to what man does to man. She was glamorous, but there was nothing glamorous about what she did. She was a paradox—a girl’s girl with a posse of devoted friends. From time to time, she would appear at someone’s door with fabulous shoes or clothes that she had spotted as a gift for a friend or cook midnight feasts for a crowd. She was a romantic drawn to another world reality, a ferocious war correspondent who refused to recognize obstacles when she went into the field. Nothing deterred her—not rocket strikes, or military censors, or the loss of balance from her vision problems. Colvin did not think in gender terms; she just got the job done and used whatever means sh

e had. She regaled her friends with stories from the field, shaped into performances that camouflaged the raw truth of her existence. After being rescued from bombings in the mountain of Chechnya—where she existed on snow and one jar of jam—she teased a friend that she could not have survived without the pricey fur the friend had pushed her to buy.

Colvin’s sangfroid and wit fit beautifully in London media and political circles, but there was a price: She battled PTSD and alcohol, and fiercely maintained a size 4, determined never to be fat, wearing La Perla in the field. She made no secret of her love of men—and she was faithful to the ones she loved. In that way, she was often and easily betrayed. Her north stars were the glamorous war correspondents who came before her. At all times, she carried Martha Gellhorn’s The Face of War, a masterwork of dispatches from Gellhorn’s decades in the field, including her on-the-ground reporting from the liberation of Dachau, where her view of corpses stacked like kindling haunted the rest of her days. Colvin, too, had a recurring nightmare—of a twenty-two-year-old Palestinian girl gunned down in a refugee camp in Lebanon. She was not interested in the strategy of war or its artillery, but rather the very real human dramas of those who suffered the consequences of what wars actually do to those who are somehow able to survive them.

* * *

A theme of basic justice links the cluster of profiles in this collection. It seems almost unnecessary to observe the obvious: I don’t like to see the innocent get railroaded or the perpetrators of evil get away with it. The length of these stories and the months spent reporting them were a gift of what is now called the golden age of magazine reporting. My editors were generous with time and resources. The essence of the craft is always the same—obsession. As a reporter, I am drawn to others as obsessed. In 1993, on assignment for The New Yorker, I wrote of Constance Baker Motley, who had helped draft Brown v. Board of Education with NAACP founder Thurgood Marshall and went on to become the first African-American woman to be appointed to the federal bench. She was a woman of quiet elegance who shopped at Lord & Taylor for a new suit before she flew to Jackson, Mississippi, to face down racist crowds outside a segregated courthouse where she argued her case to integrate the University of Mississippi in front of a mural of a plantation and its slaves memorialized on the courtroom wall. She argued case after case in Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia, bringing in crowds of African-Americans who would marvel that a woman of color was at last causing real change. In Jackson, the local paper referred to her as “that Motley woman.”

Her pursuit of justice did not incite the murderous violence that came out of the quest, twenty-five years later, of a school teacher in the Swat Valley of Pakistan who attempted to alert the world to the sadism being perpetrated by the Taliban in collusion with the powers inside Pakistan. Ziauddin Yousafzai, the father of Malala Yousafzai, almost lost his daughter in an attack that galvanized the world and turned the then-fourteen-year-old Malala into an international heroine who won the Nobel Prize.

I am also drawn to those who have been somehow caught in the vise of public events and have been shredded by overwhelming forces. The death threats and the smear campaign waged against tobacco whistleblower Jeffrey Wigand and CBS’s 60 Minutes producer Lowell Bergman as they attempted to break the story of the corporate malfeasance being perpetrated by Big Tobacco preoccupied me for months. The chilling winds that could come from corporate big footing at news organizations could only lead to censorship—as it had at CBS, which had killed Bergman’s story. Not long after, I was in Atlanta, spending days with the hapless security guard Richard Jewell, wrongly accused by the F.B.I., NBC, and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution of a terrorist attack on the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. It took Jewell months to escape from the machinations of the F.B.I. He was rescued by a quirky contrarian local lawyer named Watson Bryant who had once employed Jewell as an office boy. How could the news outlets have gotten it so wrong? Why was I not surprised?

* * *

The answer is perhaps rooted in my childhood in San Antonio. My father, feisty and opinionated, styled himself as a self-appointed one-man district attorney’s office. He was a businessman; his day job was running a small chain of discount department stores, but his hobby was exposing, as he phrased it, “the god damn hypocrites and corrupt sons of bitches” who lived around us in our leafy garden suburb. I have written before of my gratitude for the background music of my growing up years—the pounding of my father’s typewriter keys churning out furious letters to editors and the heads of the Federal Trade Commission, and the copy for the thousands of handbills that every day would be placed in the shopping bags of Solo-Serve, the discount store that was started by my grandfather, a Mexican immigrant by way of the Baltic. His mission in 1919 was revolutionary: Solo-Serve was South Texas’s first “clerkless store” and welcomed all customers, especially the Mexican-Americans who were forced to use separate entrances at Texas schools.

Who and what didn’t my father take on? The tax frauds and attempts to demolish historic Mexican-American neighborhoods for real estate development that were being perpetrated by San Antonio’s social set; the escalation of South Texas electrical power rates that would implicate a prominent local lawyer and his client, Houston’s oil magnate Oscar Wyatt, the chairman of Coastal States, who was often splashed in Vogue and Town and Country, with his wife, the ebullient social swan Lynn. Wyatt later pleaded guilty to foreign trading violations for his relationship with Saddam Hussein.

My father’s own command post was a glassed-in office on the second floor of his downtown store where he loved to bark into the public address system. “Attention, shoppers,” he once announced in his deep Texas drawl, “the chairman of the Estée Lauder Company is in our stores today in the cosmetics department trying to find out how we are able to sell his products at 50 percent off what you buy them for in New York. I want y’all to go and tell him a big Texas hello!” He came home gleeful at the melee he had caused. As an advertiser responsible for multiple pages of weekly Solo-Serve coupon specials, he was tolerated by the local newspaper editors and publishers, and beloved by reporters, who relied on him for scoops, but loathed by many of the husbands of my mother’s friends and members of our temple who were occasionally the targets of his investigations. The implicit message of my childhood was that it was our moral duty to speak out against injustice loudly and often, no matter who might be offended. I’m not sure this lesson did me any favors beyond the essential one of setting me on my path as a reporter.

There was no other profession I could choose. Tom Wolfe had thrown down the gauntlet and lured in just about anyone who had ever thought about lifting a pen, hooking us with his neon language and Fourth of July word explosions that made vivid the race car drivers and the follies of the nouveau riche and limousine liberals, including the art collector Ethel Scull, whose pineapple-colored hair and taxi fleet owner husband allowed her to buy walls of Andy Warhols. And there was Wolfe himself in Austin, speaking to a standing-room-only crowd at the University of Texas in 1969. I jammed myself into the room to hear my idol and, during the question and answer session, waved my hand until Wolfe looked my way. Then, nerves overcame me. All I could stammer was, “What did Ethel Scull think of the story you wrote about her?” The question, fifty years later, still mortifies with its naïve assumption that what anyone thinks matters, but Wolfe, always so kind and impeccable, took the time to answer. “Well, she did not like it very much,” he said. The assertion of fact with its unspoken corollary—what difference does it make?—delivered by this god in his white linen suit was, for me, the beginning of liberation.

* * *

Like Marie Colvin, I fell in love with the exhilaration of reporting, the flow state where your obsession to Get the Story makes all distractions melt away. My father lived to be almost ninety and encouraged me to go after the corporate scoundrels of the 1990s—the Brown & Williamson Tobacco Company, which poisoned its products; the Houston thugs who ran Enron; Michael Milken and his junk bond schemes; the F

.B.I. and its false accusation and tarnishing of the reputation of Richard Jewell; and the crass opportunism of New York real estate con man Donald Trump and his mentor, the moral monster and rogue darling of the New York establishment Roy Cohn. “Those sons of bitches!” he said in his last years. “How do they get away with it?”

“I would fly to Canada for a bobby pin,” one writer told me, describing her research methods, not long after I joined Vanity Fair in 1984. We were given the expense accounts and salaries to be able to do such things and were ferried about the city in sleek black town cars from a company called Big Apple. All day long they idled, tying up the traffic, firmly double-parked outside the Condé Nast Building at Madison Avenue and Forty-fourth Street. Take a subway? Why bother? It was boom time in the world of media. Anyone who had a major role in what we now quaintly refer to as “a content company”—then defined as a movie studio, a network, a talent agency, or a newspaper or magazine—was treated as if he or she was a god on Mount Olympus. Incredibly, in the atmosphere of surging magazine sales and new magazine start-ups that all attempted to describe the bonfire of 1980s vanities, we traveled the world and would linger for weeks, hoping to get a source to talk, turning in five-figure expense accounts for stories that could run eighteen thousand words. Fly to the South of France with one of the editors in hopes of snaring an interview with the deposed Haitian dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier? Not a problem. Weeks were spent near Moulin de Mougins, three-star meals charged without a thought. The interview was finally secured because of the intense vanity of Michelle Duvalier, the wife of “Baby Doc” Duvalier—Madame le President, as she insisted we call her. “Why didn’t you tell me that I would be photographed by Helmut Newton?” she asked (referring to that decade’s most celebrated chronicler of the beau monde) when we stuffed a final note inside her gate. The brazen larcenies of Michelle Duvalier, a former fashion model who appeared at our interview in a jewel-encrusted appliquéd jacket, had taken $500 million from a country where the average yearly income was $300. Mired in splendor on the Riviera, she spent much of our interview complaining because the locals hated her and she had to make dinner reservations under an assumed name—and she was forced to give her husband a manicure every fortnight.

A Private War

A Private War