- Home

- Brenner, Marie

A Private War Page 2

A Private War Read online

Page 2

On the same trip, I visited Graham Greene, perhaps the finest literary stylist of the century, in his modest one-bedroom flat in the port of Antibes. Greene wrote on a card table and was mildly irritated when I expressed surprise. “What else would I need?” he asked me. Then the man who had defined the barbaric Haiti of the Duvaliers in his masterpiece, The Comedians, said, “You can kill a conscience over time. Baby Doc proves that.”

It was not all glamorous or luxe. From time to time I felt in some degree of danger. Landing in Kabul in the summer of 2004, there were explosions nightly and a guard posted outside my door. “Keep your windows closed,” my fixer, Samir, cautioned as we drove into Herat in search of a warlord and anyone who could tell us anything about the location of Osama Bin-Laden. My reporting in that period as well took me to the most dismal areas in the outskirts of Paris, where the police often failed to respond to crime. There, I found a terrified group of Muslim women trying to assimilate. Their terror was of their families, who insisted that they marry and return to Algeria or Tunisia, to remain in a more traditional life. Their fear was real—already five thousand French women reportedly had been virtually kidnapped, as France grappled with its failure to come to embrace their immigrant population.

* * *

As I write in June of 2018, America and the world are in the grip of a political and cultural civil war, ramped up by the machinations of a president who appears untethered from any sense of legal reality, respect for our institutions, or moral core. As corrupt as the Duvaliers, he has installed his children in positions of power and enrichment. The frame of our daily life is now dictated by the scolds and pronouncements of cable TV and the urgencies of infotainment news that helped to create Trump and define the era. All of this was done with the implicit acquiescence of a New York establishment that helped Trump rise to power, pushing his buffoon antics into frequent headlines in the 1980s and 1990s while reporting in whispers to each other his vulgar asides, as if the display of his id was somehow an art form.

Perhaps it was. His ghostwriter Tony Schwartz perpetrated the Trump myth in The Art of the Deal, baffling his colleagues for his willingness to sign on as a Trump biographer. Eventually he realized that he had helped to create “a Frankenstein who got up from the table,” as former New York editor Edward Kosner phrased it. That phrase would be used and used again, as well as all the others that have defined this era—“we are beyond the tipping point”; “we are in uncharted territory”; “he doesn’t know what he doesn’t know”—and have been rendered meaningless by the constant barrage of cable TV against forces that cannot be shamed or, as of this moment, stopped.

I was reporting for Ed Kosner and his New York in 1980, just after Trump burst onto the scene. It was a moment when the city still hovered in the twilight of a world controlled by the Tammany bosses and the Favor Bank politics of the party bosses. The elite old-money values of the WASP power structure were evaporating. Few would mourn the passing of their predatory monopolies and quotas—or almost complete exclusion of women and minorities in jobs, clubs, and real estate. The ad “You don’t have to be Jewish to love Levy’s Rye Bread” seemed revolutionary when it appeared in the 1960s, but the snobberies and anti-Semitism depicted in Gentleman’s Agreement seemed almost as relevant a decade later. Soon all of that would change: We were hovering on the edge of the volcano of deregulation brought by newly elected president Ronald Reagan and the greed and glory of the Wall Street buccaneers. Trump rode the gossip columns, shamelessly called the columnists pretending to be a Trump PR man, and charmed his way into Manhattan with his rogue antics. For a generation that had grown up in the sixties, the kid from Queens sticking his fingers in the eyes of authority was catnip, and we could not get enough of him. “I called Trump every time I wanted to juice up my copy,” the New York Times reporter Maggie Haberman said recently.

Trump was, for all of us, irresistible, even as a target. Everything about him was fishy, I wrote in 1980, not least his antics in getting the Hyatt hotel developed in a desolate part of Forty-second Street near Grand Central Terminal. He spoke to his lawyer Roy Cohn at least “a dozen times a day,” Cohn preened from his shambles of an office with dusty stuffed frogs decorating every surface. He was obsessed with his young protégé. “Donald can’t make a move without me,” Cohn said, as if he wished they were lovers. Trump had transferred from Fordham to the Wharton School, where my older brother Carl was in his class. Learning I had been assigned to write about him, my brother laughed. “That jerk. He had no friends and rode around in a limousine talking about his father’s deals in Queens.” At the time, the future actress Candice Bergen was also at Penn. Trump called her for a date and appeared, she later remembered, in a maroon jacket that matched his limousine. “I’m a vegetarian,” she told him. “That’s good,” he said. “We are going to a steak house.” He was all id, even then, a man-child trying to hide what seemed to be anxiety about himself. By the time he was in his thirties, the bully-boy tactics and flouting of all rules began to leak into public view, but the lack of censure of his corrosive persona was impossible to predict. The bankruptcies and financial shenanigans that sank his empire in 1990 will be seen as predictive when the Trump bubble finally bursts. America will be affected for decades to come.

I mentioned the ways subjects respond to profiles. I wrote a piece about Donald Trump in Vanity Fair in 1990, as Trump’s world seemed about to collapse. He was close to bankruptcy and had left his wife Ivana, moving to a separate apartment at the Trump Tower, where he was reportedly spending his day eating hamburgers and fries in front of a large TV. I have never written about Trump’s reaction to my reporting. Upset that I reported for Vanity Fair that he kept a copy of My New Order, Hitler’s speeches and pronouncements, by his bed, Trump went on a rampage, appearing with anchorwoman Barbara Walters in prime time to announce he was suing me. Of course he never did. Instead, for a decade, he attacked me as “an unattractive reporter with men issues” in the tabloids, and in his own book, Trump: The Art of the Comeback. I am happy to report that he described “After the Gold Rush” as “one of the worst stories ever written about me.”

And that brings us to the wine. Since 1991, the wine Trump may or not have poured down my dress—or over my head, in one Trump retelling—has changed color and amount depending on who recounts the tale. Trump told New Yorker writer Mark Singer that he threw red wine on me. Singer was gallant enough not to report whatever else he said.

Trump’s inability to tell the truth extended even to misstating his form of revenge on my reporting.

At a charity dinner, almost a year after my twelve-thousand-word story appeared, Trump slipped behind me as I sat with friends and took a half glass of white wine and poured it down my black jacket. I thought it was a waiter and did not flinch, but the faces at the table froze in horror. Trump scurried out the door, a coward’s coward, incapable of even facing me. I will never be able to express my gratitude for Trump’s remark to Mark Singer. That half glass of wine has become a badge of honor.

What was it that really angered Donald Trump in “After the Gold Rush”? The fact that he had grifted—among others—his close associate Louise Sunshine, who had to borrow $1 million from her friend the developer Leonard Stern to retain property rights in one of his buildings? Or that his children did not speak to him? The detail that stays with me occurred in the press room of the New York State Courthouse in lower Manhattan. Trump was fighting a brutal case brought against him by scores of Polish immigrant workers who allegedly had been paid under the minimum wage to build the Trump Tower. The tabloids had turned on Trump, accusing him of paying “slave wages,” exploiting the Polish workers. Trump settled, at a cost, it was said at the time, of millions of dollars. I made my way to the press room to hear my colleagues erupt in rage, at themselves and at the man to whom they had devoted so much ink. The babble in 1990 seemed definitive: “We made this monster. We gave him the headlines. We created him. Never again.”

* * *

>

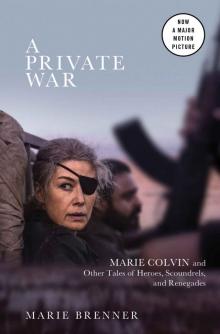

The piece I wrote about Marie Colvin—“A Private War”—has been made into a movie. In January of this year, I visited the set. It was snowing in England that day outside London. The movie A Private War was being directed by Matt Heineman, adapted from my piece. Heineman, just 34, had been nominated for an Oscar for his documentary Cartel Land, but had never made a feature. He had however directed a searing film—City of Ghosts—detailing the lives of several of Syria’s citizen reporters. He was galvanized by Marie’s career and for three years had worked tirelessly to bring her life story to the screen.

The newsroom of the Sunday Times of London had been meticulously re-created to look like the newsroom that Marie Colvin worked from. I was there to see the actress Rosamund Pike playing Colvin. On the day I visited, a pivotal scene was being filmed. Colvin was determined to get herself assigned to Sri Lanka in April of 2001 to cover a yet unreported scene of hundreds of thousands of refugees who were under siege by government forces. She had a shouting match with her editor in the newsroom. He wanted her to write about the leader of the PLO, Yasser Arafat; she insisted she would go to Sri Lanka. He was furious she had run up $56,000 in SAT phone charges. The Sri Lanka decision was catastrophic for Colvin: She would lose the sight in an eye to a grenade thrown at her when she announced she was a reporter and wear an eye patch for the rest of her life.

The afternoon I spent on the set was unnerving, as I knew what was coming for Colvin once she left the safety of the London newsroom. It was for me a time warp on many levels, not least of which was the atmosphere of the Sunday Times. Struggling as a freelance foreign correspondent in the London of the late 1970s, I had the immense good fortune to be befriended by the legendary Sunday Times editor Harold Evans, whose investigations into the horrors of thalidomide and the unmasking of the elite spies Kim Philby and Anthony Blunt inspired not only my reporting but also Colvin’s. Evans had fallen in love with a young writer, Tina Brown, and had brought her to dinner. “Use my telex room any time you want to send your copy,” Evans told me. “Just take the telex operator a bottle of scotch and tell them I said it was okay.” Evans was at the top of his game—the foreign correspondents of the Sunday Times were dispatched to every remote war in the world.

That night would begin a long and enduring friendship and two decades of reporting for Tina during her eventual tenure at Vanity Fair. Two of these stories—including “After the Gold Rush”—were written with Tina’s strong encouragement and editorial hand, Wayne Lawson’s sharpened red pencils and rigor enhanced every word I wrote for three decades at the magazine. Trying to close Trump, my fax machine blipped out all hours of the night with Tina’s notes. “Not there yet—” “What does——prove?” “You need more sources.” I tried to sleep but heard the beep of the fax machine until dawn. “Can you get more inside?” “Can you go deeper and more reflective? It needs more you.” She was right—and is responsible for the macabre final scene at the courthouse.

If you are lucky as a reporter, you get that kind of editing—and the ethical judgments that accompany it. In 1995, I returned to Vanity Fair from The New Yorker to write about the hypocrisy of CBS killing a 60 Minutes episode that featured a mysterious tobacco whistleblower—so as-yet-unknown that we called him Jeffrey “Wee-gand.” I had gone back to work at Vanity Fair at the gracious invitation of Graydon Carter, whom I had only briefly worked with before. At a lucky lunch with a close friend named Andrew Tobias, an anti-tobacco activist and later the Democratic National Committee treasurer, Andy quickly set me on the right course on the subject of Jeffrey Wigand. “It’s not about CBS. It’s about who is the whistleblower and what does he know?” he said. I took that back to Carter, who said, “Christ. Let me find out how much advertising we get from Brown & Williamson.” He came back the next day. “Go for it. It’s only $500,000.”

It took weeks to discover that “Wee-gand” was in fact pronounced “WY-gand,” and that he was being smeared by John Scanlon, a genial public relations man who had taken $1 million from Brown & Williamson to demolish Wigand’s reputation. Scanlon was a close friend of Carter’s as well as a Vanity Fair consultant. “I can’t go forward with this unless John is put on leave,” I told Carter, unsure of his reaction. He did not hesitate. “He is out as of now,” he said. Their friendship would never fully recover, but Carter did not change a word of the lengthy description of Scanlon and his machinations detailed in the eighteen-thousand-word “The Man Who Knew Too Much.”

Carter stayed at Vanity Fair for twenty-five years and sent me to India to report on 26/11 and the terrorists who overtook the Taj Palace in Mumbai; to France, on multiple occasions, to report on the rise of anti-Semitism; to Afghanistan; and to England to chronicle the life of Marie Colvin. He knew legal dramas attracted me and called when one caught his attention—Richard Jewell; the savaging of the Haitian immigrant Abner Louima by a New York City police detective; the build up to the Iraq War in 2003. Over the years, we did dozens of stories together, several of which would be beautifully edited by Wayne Lawson’s successor, Mark Rozzo. A few years ago, Graydon collected them and presented them to me in a stylish leather-bound volume that he had archly titled Dynasties, Angels and Compromising Positions. On the spine, I saw his display title: The Brenner Years in Vanity Fair. The reporter in me wondered: was he telling me to retire? He was not.

Our last story together was the profile that closes this collection: Graydon and my current editor David Friend divined it was time to revisit the history of Trump’s mentor Roy Cohn and his long, sordid association with his final prodigy, Donald Trump. As always with Graydon, an elegant typed thank-you on a Smythson’s card appeared after the story was published. This one was particularly poignant. Graydon had made the decision to retire, but I did not know it yet. He had written profoundly and at length, month after month, in his editor’s letter, about the rise of the moral monsters around Trump and felt the time had come to move on. In his note, he seemed almost sentimental about the rogues and con men that had fed both our careers. How had we both started out thinking and writing about Roy Cohn and Donald Trump, and how could we still be grappling decades later with their legacy? “To think it would all resurface today,” he noted, restraint hardly disguising the emotions he kept in check.

MARIE COLVIN’S PRIVATE WAR

AUGUST 2012

“They just don’t make men like they used to.”

“Why the fuck is that guy singing? Can’t someone shut him up?” Marie Colvin whispered urgently after dropping into the long, dark, dank tunnel that would lead her to the last reporting assignment of her life. It was the night of February 20, 2012. All Colvin could hear was the piercing sound made by the Free Syrian Army commander accompanying her and the photographer Paul Conroy: “Allahu Akbar. Allahu Akbar.” The song, which permeated the two-and-a-half-mile abandoned storm drain that ran under the Syrian city of Homs, was both a prayer (God is great) and a celebration. The singer was jubilant that the Sunday Times of London’s renowned war correspondent Marie Colvin was there. But his voice unnerved Colvin. “Paul, do something!” she demanded. “Make him stop!”

For anyone who knew her, Colvin’s voice was unmistakable. All her years in London had not subdued her American whiskey tone. Just as memorable was the cascade of laughter that always erupted when there seemed to be no way out. It was not heard that night as she and Conroy made their way back into a massacre being perpetrated by the troops of President Bashar al-Assad near Syria’s western border. The ancient city of Homs was now a bloodbath.

“Can’t talk about the way in, it is the artery for the city and I promised to reveal no details,” Colvin had emailed her editor after she and Conroy made their first trip into Homs, three days earlier. They had arrived late Thursday night, thirty-six hours away from press deadline, and Colvin knew that the foreign desk in London would soon be bonkers. The day before she walked into the apartment building in Homs where two grimy rooms were set up as a temporary media center, the top floor had been sheared o

ff by rockets. Many thought the attack had been deliberate. The smell of death assaulted Colvin as mutilated bodies were rushed out to a makeshift clinic blocks away.

At 7:40 a.m., Colvin had opened her laptop and emailed her editor. There wasn’t a hint of panic or apprehension in her exuberant tone: “No other Brits here. Have heard that Spencer and Chulov of the Torygraph [Private Eye’s nickname for the Telegraph] and Guardian trying to make it here but so far we have leapfrogged ahead of them. Heavy shelling this morning.”

She was in full command of her journalistic powers; the turbulence of her London life had been left behind. Homs, Colvin wrote a few hours later, was “the symbol of the revolt, a ghost town, echoing with the sound of shelling and crack of sniper fire, the odd car careening down a street at speed. Hope to get to a conference hall basement where 300 women and children living in the cold and dark. Candles, one baby born this week without medical care, little food.” In a field clinic, she later observed plasma bags suspended from wooden coat hangers. The only doctor was a veterinarian.

Now, on her way back into Homs, Colvin moved slowly, crouching in the four-and-a-half-foot-high tunnel. Fifty-six years old, she wore her signature—a black patch over her left eye, lost to a grenade in Sri Lanka in 2001. Every twenty minutes or so, the sound of an approaching motorcycle made her and Conroy flatten themselves against the wall. Conroy could see injured Syrians strapped on the backs of the vehicles. He worried about Colvin’s vision and her balance; she had recently recovered from back surgery. “Of all the trips we had done together, this one was complete insanity,” Conroy told me.

A Private War

A Private War